In a new examine, researchers from the College of Tokyo, Harvard College, and the Worldwide Analysis Middle for Neurointelligence have unveiled a method for creating lifelike robotic pores and skin utilizing residing human cells. As a proof of idea, the workforce engineered a small robotic face able to smiling, lined totally with a layer of pink residing tissue.

The researchers word that utilizing residing pores and skin tissue as a robotic overlaying has advantages, because it’s versatile sufficient to convey feelings and might probably restore itself. “Because the function of robots continues to evolve, the supplies used to cowl social robots must exhibit lifelike features, similar to self-healing,” wrote the researchers within the examine.

Shoji Takeuchi, Michio Kawai, Minghao Nie, and Haruka Oda authored the examine, titled “Perforation-type anchors impressed by pores and skin ligament for robotic face lined with residing pores and skin,” which is due for July publication in Cell Experiences Bodily Science. We discovered of the examine from a report printed earlier this week by New Scientist.

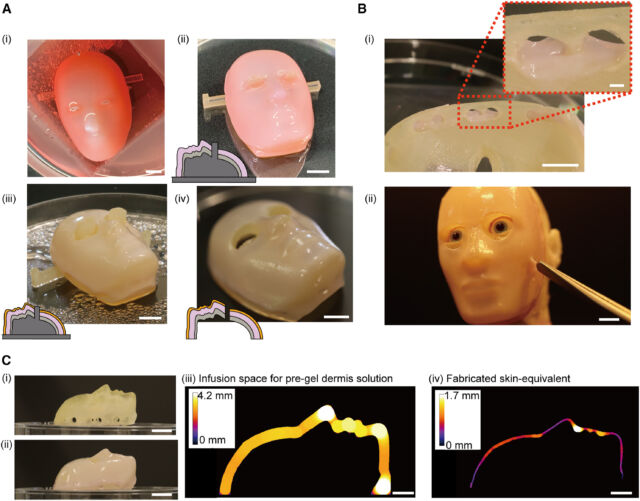

The examine describes a novel technique for attaching cultured pores and skin to robotic surfaces utilizing “perforation-type anchors” impressed by pure pores and skin ligaments. These tiny v-shaped cavities within the robotic’s construction permit residing tissue to infiltrate and create a safe bond, mimicking how human pores and skin attaches to underlying tissues.

To display the pores and skin’s capabilities, the workforce engineered a palm-sized robotic face capable of type a convincing smile. Actuators linked to the bottom allowed the face to maneuver, with the residing pores and skin flexing. The researchers additionally lined a static 3D-printed head form with the engineered pores and skin.

Takeuchi et al. created their robotic face by first 3D-printing a resin base embedded with the perforation-type anchors. They then utilized a combination of human pores and skin cells in a collagen scaffold, permitting the residing tissue to develop into the anchors.